[ad_1]

How many fewer calories have to be consumed daily to shed a single pound of body fat?

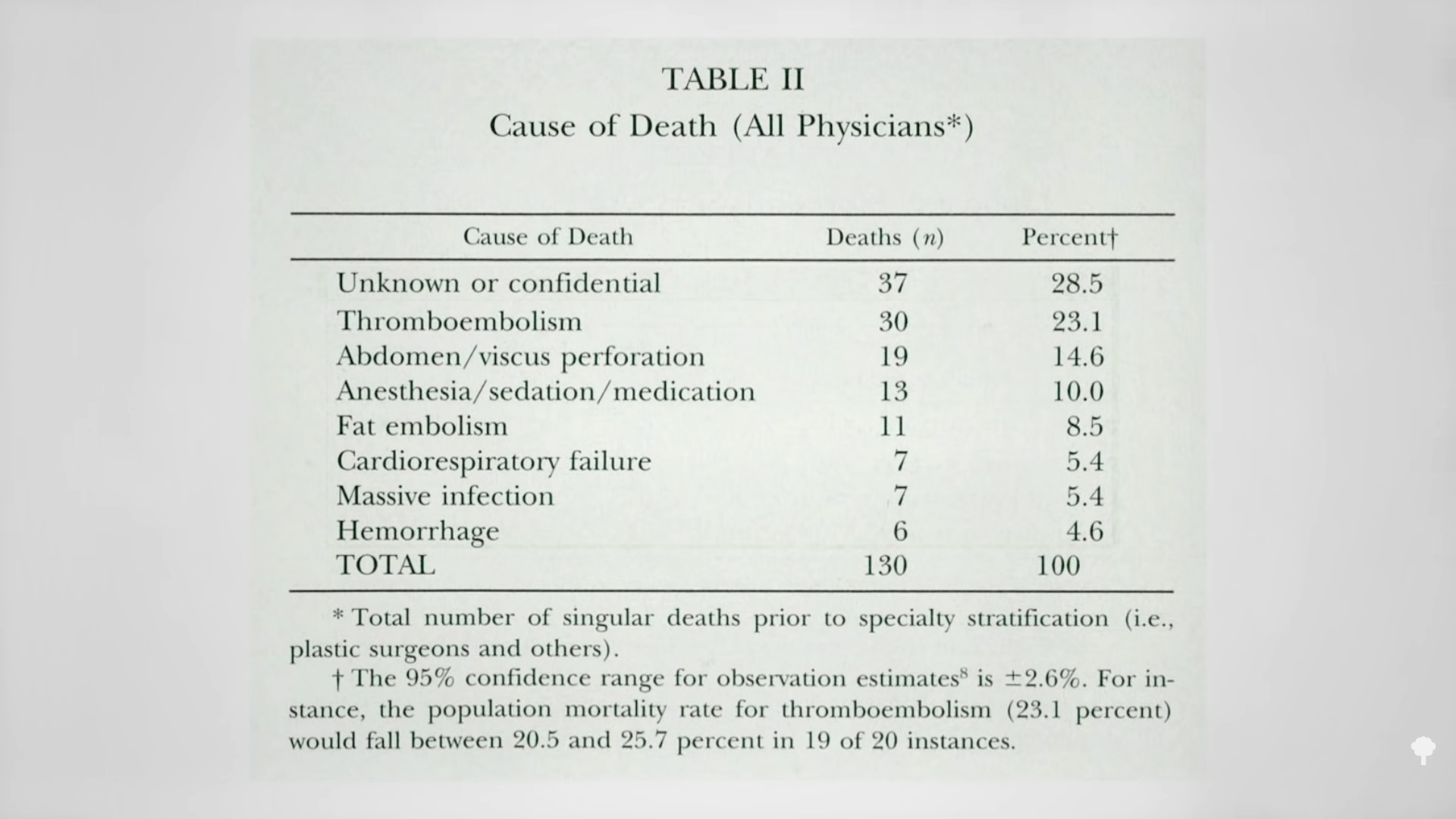

The inaugural surgical endeavor related to physical reshaping took place in 1921, involving a dancer desiring to enhance the contour of her ankles and knees. Regrettably, the intervention led to excessive tissue removal and excessively tight sutures, causing tissue death, amputation, and marking the earliest documented instance of medical negligence in the realm of plastic surgery. Present-day liposuction procedures are notably safer, with only around 1 in 5,000 patients succumbing, predominantly due to indeterminate reasons like a clot reaching the lungs or accidental perforation of internal organs. A comprehensive “Cause of Death” chart can be seen below and at 0:37 in my video The 3,500 Calorie per Pound Rule Is Incorrect.

Liposuction presently stands as the most sought-after cosmetic surgery globally, however, its impacts are purely superficial. An investigation published in the New England Journal of Medicine evaluated obese women before and after undergoing approximately 20 pounds of fat removal, yielding an almost 20 percent reduction in total body fat. Ordinarily, shedding just 5 to 10 percent of body weight in fat results in noteworthy enhancements in blood pressure, blood sugar levels, inflammation, cholesterol, and triglycerides. However, the results of liposuction were inconclusive. None of these advantages were discernible even after extensive fat removal, indicating that the issue is not the fat underneath the skin, referred to as subcutaneous fat. The metabolic detriments of obesity stem from the visceral fat, the fat surrounding or infiltrating internal organs, akin to the fat interspersed in muscles and the liver. The process of eliminating this hazardous fat involves consuming fewer calories than the body expends.

Those familiar with the television show The Biggest Loser are aware that through substantial calorie restriction and physical activity, significant weight loss can be achieved. Similarly, there are documented instances in medical literature of what some term as “extreme obesity.” In one case, an individual managed to drastically reduce weight “mainly without professional intervention and sans surgery” and maintained the change for years. He shed 374 pounds, averting roughly 20 pounds monthly by cycling for two hours per day and limiting daily intake to 800 calories, which is akin to the rations provided at concentration camps during World War II.

Possibly one of the most prominent weight loss achievements documented on television was Oprah’s. She exhibited a container brimming with fat symbolizing the 67 pounds she lost following a very-low-calorie diet plan. How many calories did she need to curtail to attain that weight reduction in four months? Consulting reputable nutrition textbooks or resources such as the Mayo Clinic reveals the elementary weight loss principle: 1 pound of fat equals 3,500 calories. Citing the Journal of the American Medical Association, it states, “A total of 3500 calories equals 1 pound of bodyweight. This implies that by diminishing (or augmenting) your intake by 500 calories daily, you will shed (or gain) 1 pound per week. (500 calories daily × 7 days = 3500 calories.)”

This simple weight-loss concept is, however, inaccurate.

The origins of the 3,500-calorie guideline can be traced back to a paper issued in 1958. The author observed that as adipose tissue in the human body consists of 87 percent fat, one pound of body fat would encompass approximately 395 grams of pure fat. Multiplying this by nine calories per gram of fat yields the estimated “3,500 calories per pound.” The significant drawback leading to “dramatically exaggerated” weight-loss forecasts is that the 3,500-calorie rule disregards the fact that alterations in the Caloric-Intake aspect of the energy-balance equation automatically result in changes in the Caloric-Expenditure aspect, such as metabolic adaptation, the decrease in metabolic rate accompanying weight loss. This is one of the contributing factors to weight loss reaching a plateau.

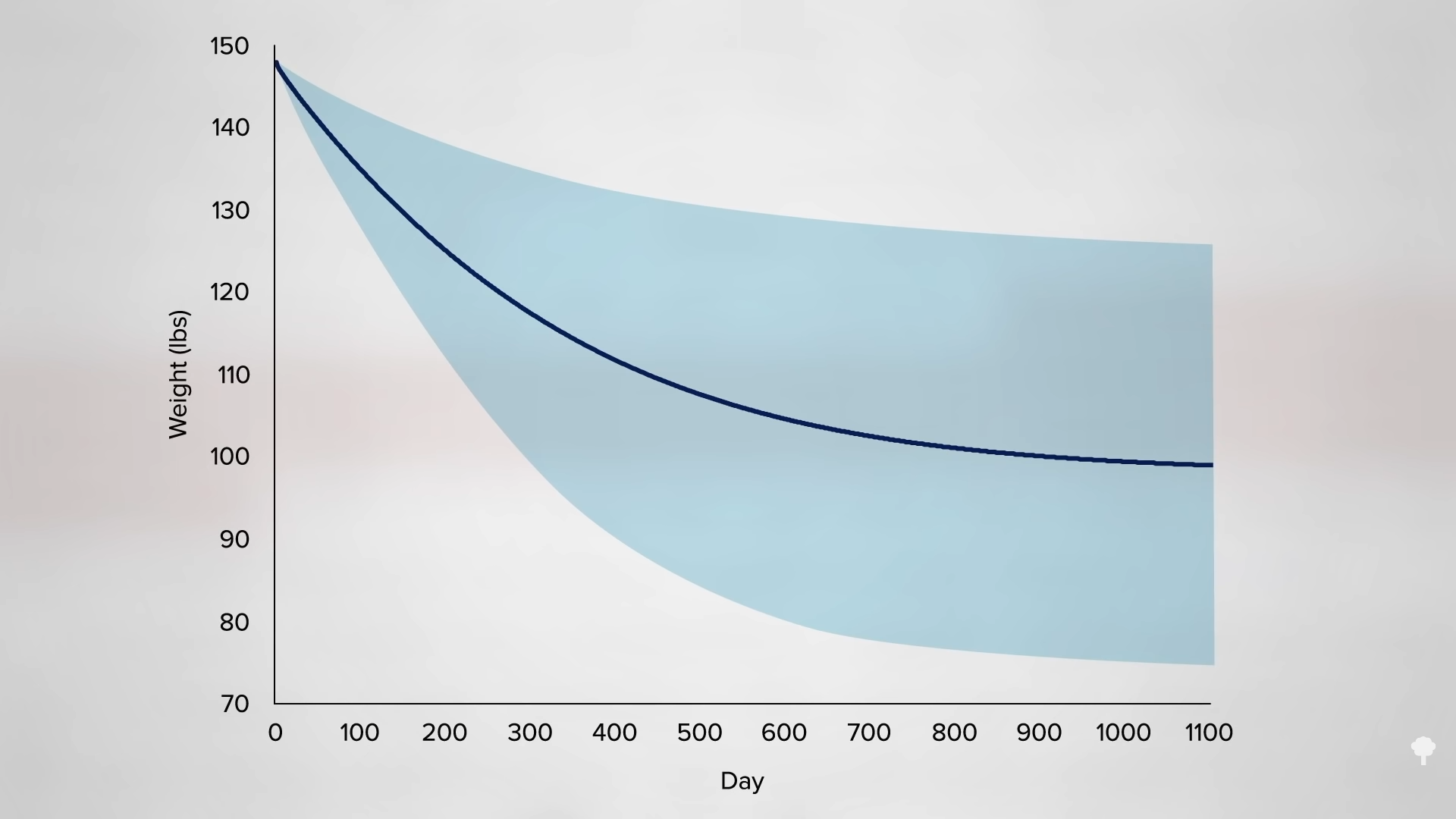

Visualize a sedentary woman of standard stature and weight aged 30. According to the 3,500-calorie rule, a reduction of 500 calories from her daily diet would translate to a loss of one pound weekly or 52 pounds per year. In three years, she would vanish, diminishing from 150 pounds to -6. Obviously, this does not occur. Instead, as illustrated in the chart below and at 4:33 in my video, in the first year, she would likely shed 32 pounds, not 52. Subsequently, after a cumulative three years, she would possibly stabilize around 100 pounds. This is attributable to the lowered calorie requirements of a leaner individual.

A portion of this disparity is attributable to “basic mechanics”: A larger amount of energy is needed to move a heavier mass, akin to the heightened fuel consumption of a Hummer compared to a compact car. Contemplate the additional effort demanded to rise from a seat, traverse a room, or ascend a few stairs while carrying a 50-pound backpack. Even during a state of rest or slumber, there is less body mass to maintain as weight decreases. Each pound of lost fat tissue implies a reduction in the volume of blood vessels needing blood circulation. Therefore, the minimal maintenance and movement requirements of slimmer bodies necessitate fewer calories. As one loses weight by consuming less, the body consequently demands less energy. This is unaccounted for by the 3,500-calorie rule.

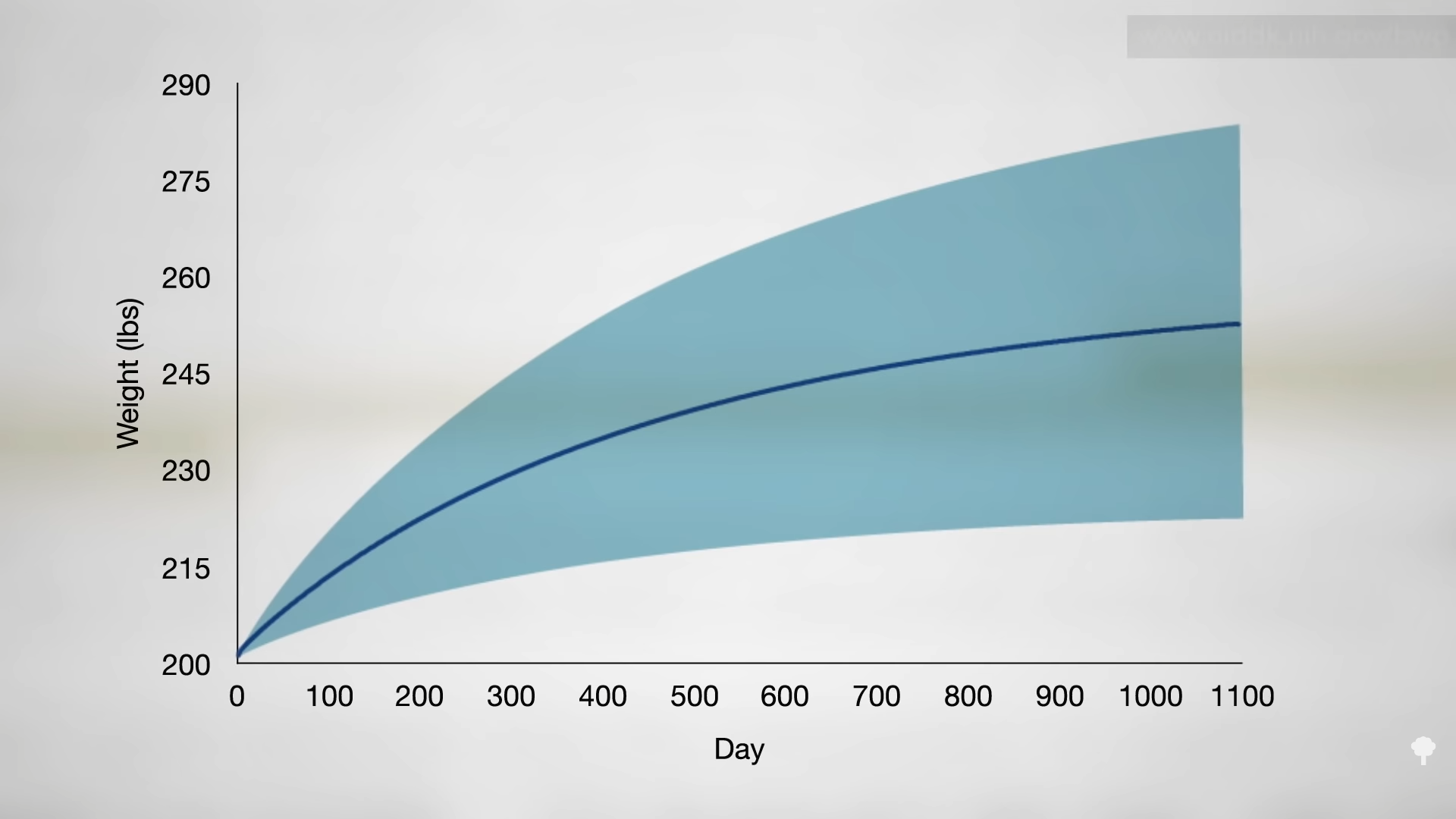

Consider it from an alternate perspective: A 200-pound man begins consuming an extra 500 calories daily, possibly from consuming a large soda or two donuts. As per the 3,500-calorie rule, in a decade, he would tip the scales at over 700 pounds. This is implausible because, the heavier he becomes, the greater the caloric expenditure simply due to existing. In essence, if you are 100 pounds overweight, the strain on the body resembles a slender individual trying to navigate while carrying 13 gallons of oil or lugging a bag laden with 400 sticks of butter. As delineated in the graph below and at 6:13 in my video, maintaining a weight of 250 pounds necessitates the equivalent energy increase of about two donuts, signaling a point of equilibrium if this pattern persists. When you have a specific calorie surplus or deficit, weight gain or loss follows a pattern that levels out over time, as opposed to a linear trajectory.

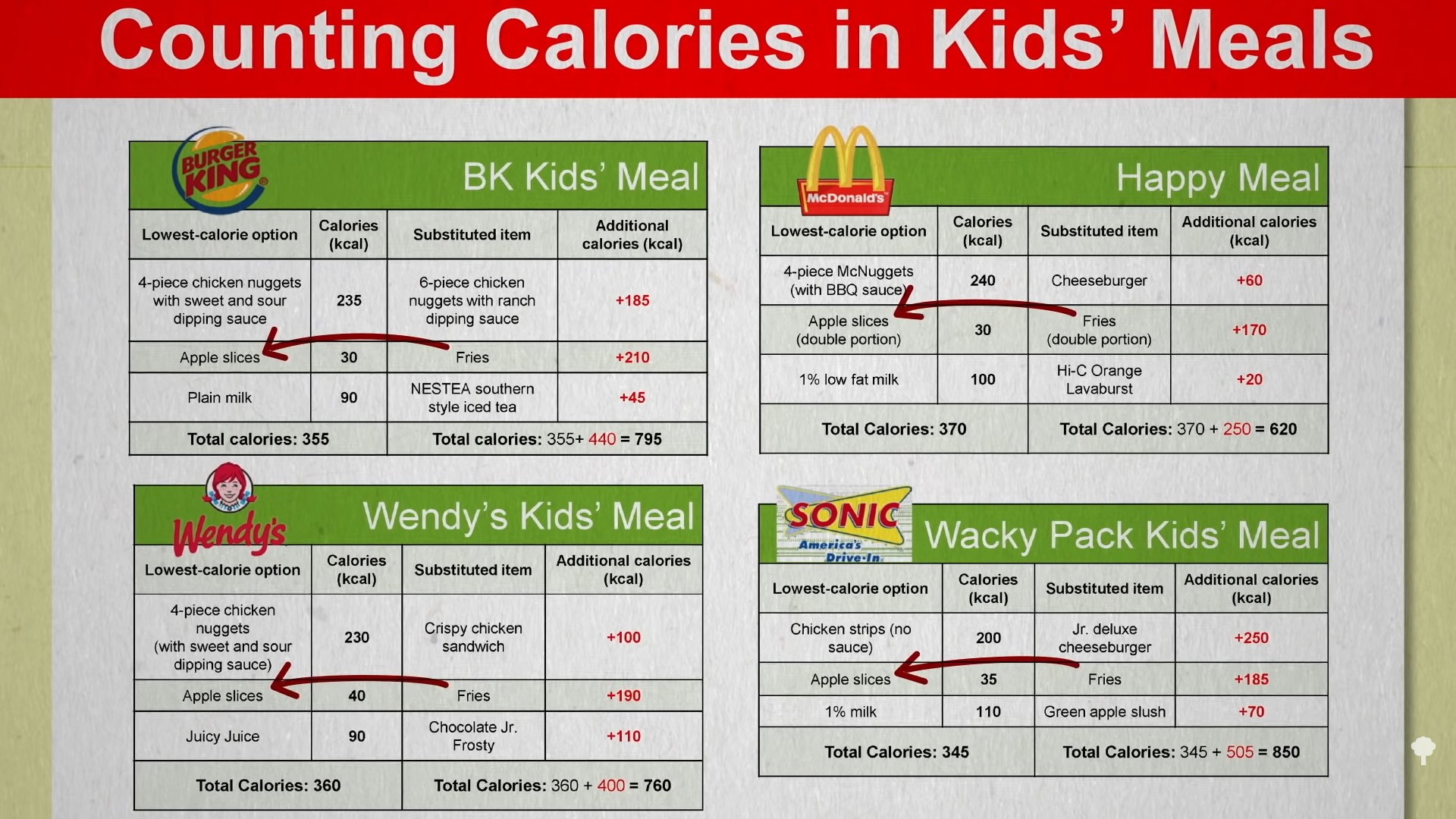

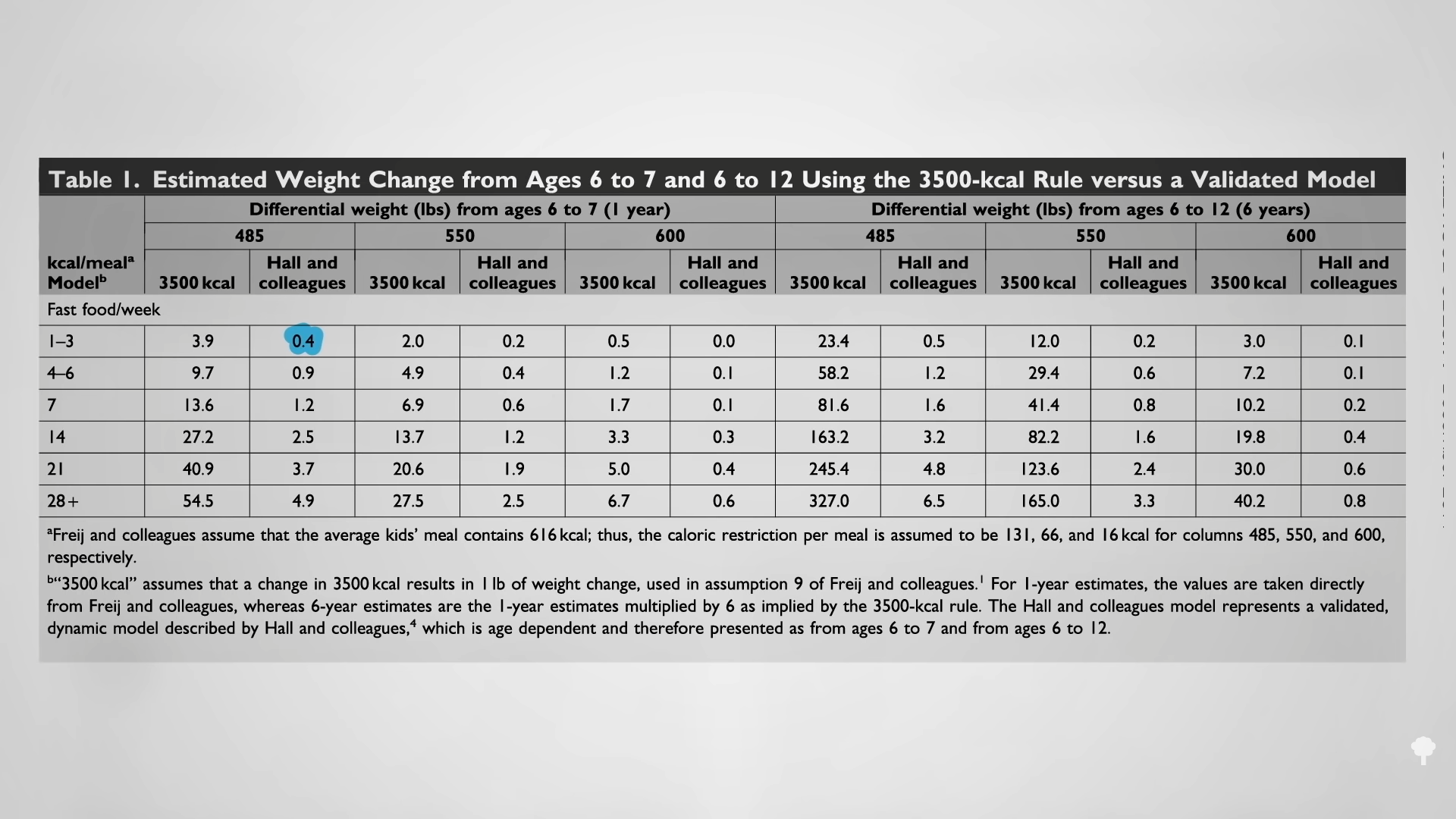

However, the 3,500-calorie rule persists, even in publications on obesity. Public health analysts utilized it to compute potential weight loss per year in children, for instance, if fast-food kids’ meals exchanged french fries with apple slices. The “Counting Calories in Kids’ Meals” visual can be observed below and at 6:39 in my video.

They approximated that two meals per week might equate to approximately four pounds annually. Nonetheless, the actual variance, as funded researchers from the National Restaurant Association were quick to point out, would likely be less than half a pound — a tenth of what the 3,500-calorie rule predicts, as illustrated below and at 7:06 in my video. The initial article was subsequently retracted.

The 3,500 Calorie per Pound Rule Is Incorrect is the first part of my fasting series, incorporating 14 videos, for which I conducted two webinars. The videos are accessible on NutritionFacts.org, or can be obtained collectively in a digital download at Intermittent Fasting. I also covered content in my webinars on Fasting and Disease Reversal and Fasting and Cancer.

Additional videos in this series can be found in the related videos section below.

Explore some other popular videos on weight loss.

I also recently delved into the ketogenic diet.

Click here to get Blue Heron Health News at discounted price while it’s still available…

[ad_2]

4 Comments

Hi there! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with Search Engine Optimization? I’m

trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not

seeing very good gains. If you know of any please

share. Many thanks! You can read similar blog here: Eco wool

Good day! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my website to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good results.

If you know of any please share. Many thanks! I saw similar text here:

Your destiny

I’m really inspired together with your writing abilities as well as with the format on your blog. Is that this a paid topic or did you customize it your self? Anyway stay up the excellent quality writing, it is uncommon to look a great blog like this one nowadays. I like nutrigladiators.com ! It’s my: HeyGen

I am really impressed together with your writing talents and also with the format in your weblog. Is that this a paid topic or did you customize it your self? Anyway stay up the nice quality writing, it is uncommon to see a great weblog like this one these days. I like nutrigladiators.com ! I made: Snipfeed